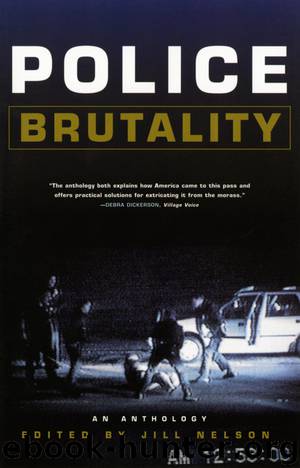

Police Brutality by Jill Nelson

Author:Jill Nelson

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

Published: 2014-02-20T16:00:00+00:00

“What Did I Do to Be So Black and Blue?”*

Police Violence and the Black Community

KATHERYN K. RUSSELL

But that was not all there was to see.

—Toni Morrison, “Dead Man Golfing” (1997)1

Tyrone Guyton. This was the first name I connected with police brutality. Guyton was a fifteen-year-old Black boy who fled the scene of a robbery. He was shot in the back by a White police officer in Oakland, California, in 1973. I was twelve years old at the time. I knew Guyton had done something wrong, but even to my young mind, the punishment did not fit the crime. This was long before I was steeped in knowledge about police, race, and crime. Concepts such as “police brutality,” “excessive force,” “probable cause,” and “racial profiling”—which I would later learn about in law school and in life—were unknown to me. Shot in the back by the police. I had a vague, yet distinct sense that a gross wrong had occurred. I did not know that Tyrone Guyton was just the latest in a centuries-long line of African Americans who had been killed by the police.

Twenty-six years later, reflecting on the ever-volatile relationship between the police and Black folks, I have a much clearer perspective. Even though the problem of police brutality is real, there remains a public haze, thick and oppressive, that surrounds the issue. It is necessary to cut through this haze, chart a road map through the current discourse on police brutality, and in the process challenge what have been passed off as the social facts about police brutality. The above epigram by Toni Morrison concisely states the problem with mainstream analyses of police brutality and other race-related issues: they are narrow, one-sided, and ultimately misleading.

It’s a Black thing. You wouldn’t understand.

—popular 1980s slogan

There are some social terms and concepts that lose or gain currency over time. In some instances, the degree of the loss or gain is directly proportional to the term’s “racial weight.” This figurative weight is based upon how closely the public links a certain issue to a particular racial group.

Most people, for example, readily associate affirmative action with African Americans. Likewise, issues of race and crime almost never center on Whites and crime; rather, they typically refer to Blacks or Latinos and crime. This racial reductionism is nowhere more apparent than in media portrayals of welfare. The popular perception is that poor, lazy Black people are draining the nation’s coffers with their monthly welfare checks.

Affirmative action, crime, and welfare have acquired their own racial baggage. More to the point, each has a Black weight. When an issue becomes a “Black thing”—something readily identified with Blacks and Blackness—a predictable set of events is set in motion. Like clockwork, the issue loses its public currency and is turned on its head. Once the issue becomes bogged down by Blackness, it quickly rises to the level of a serious social problem and, finally, leads to social, legislative, or political action (e.g., California’s anti–affirmative action Proposition 209, President Clinton’s “Mend it, don’t end it” position on affirmative action).

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| General | Discrimination & Racism |

Nudge - Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Thaler Sunstein(7676)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5407)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5397)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4549)

The Sports Rules Book by Human Kinetics(4363)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(4355)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(4232)

Captivate by Vanessa Van Edwards(3826)

Mummy Knew by Lisa James(3669)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3520)

The Worm at the Core by Sheldon Solomon(3467)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3449)

The 48 laws of power by Robert Greene & Joost Elffers(3200)

Suicide: A Study in Sociology by Emile Durkheim(3001)

The Slow Fix: Solve Problems, Work Smarter, and Live Better In a World Addicted to Speed by Carl Honore(2986)

The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell(2889)

Humans of New York by Brandon Stanton(2857)

Handbook of Forensic Sociology and Psychology by Stephen J. Morewitz & Mark L. Goldstein(2685)

The Happy Hooker by Xaviera Hollander(2678)